Audio

2015 Founders Conference w/ Commentary

On 30, Sep 2015 | In Audio, Jeffery Johnson, Pascal Denault, Resources | By Brandon Adams

2015 SOUTHERN BAPTIST FOUNDERS CONFERENCE—SOUTHWEST

HOSTED BY: HERITAGE BAPTIST CHURCH, Mansfield, Texas

The Distinctives of Baptist Covenant Theology

SEPTEMBER 24-25, 2015

2015 Founders Conference on SermonAudio.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This conference was a great encouragement to 1689Federalism.com. 2 years ago very few people were aware of this view and now people are gathering together at a conference to learn more about it. Lord willing, this trend will continue.

Due to some of the material presented in the lectures, some comments will be offered.

Contemporary Challenges

Jeffrey Johnson helpfully outlined 3 contemporary challenges: Ignorance (many people are still not aware of it), Identity (what are the essential points), Intolerance (danger of splintering). His helpful list of the essential points of 1689 Federalism was:

- There was a pre-fall covenant made with Adam, and it was the Covenant of Works

- There is a dichotomy to the Abrahamic Covenant

- The Old Covenant is a republication of the Covenant of Works

- The third use of the moral law

- The New Covenant alone is the Covenant of Grace (the most essential point)

This is a good list, but points 2 and 3 require some commentary.

First, in regards to Abraham, Johnson quotes Coxe, Collins, and Spilsbury. When Collins says “We must know the Covenant made with Abraham had two parts” he goes on to clarify “First, a spiritual, which consisted in God’s promising to… all his Spiritual-Seed… that through Jesus Christ [they] should have their Faith counted for Righteousness.” And “Second, This Promise consisted of temporal good: so God promised Abraham’s Seed should enjoy the (i) Land of Canaan, and have plenty of outward blessings, so sealed this Promise by Circumcision.”

When Spilsbury says “There was in Abraham at that time a spirituall seed and a fleshly seed. Between which seeds God ever distinguished through all their Generations.” he goes on to specify what concerned the fleshly seed “Now these being the particular expressions of the covenant, and as they lie barely in the letter, they are figurative speeches, and so considered onely as they were temporall, for so was Canaan a temporall inheritance, and so were the other outward blessings, under which were figured out spiritual substances, onely to the like Subjects. And as they were outwrad or temporal, so considered, they were both generall and conditional; for as the people did then believe God, and obey him, so they did enjoy them, and not else, as Heb. 3.”1

When Coxe says “Abraham is to be considered in a double capacity: he is the father of all true believers and the father and root of the Israelite nation.” He goes on to say “God entered into covenant with him for both of these seeds and since they are formally distinguished from one another, their covenant interest must necessarily be different and fall under a distinct consideration. The blessings appropriate to either must be conveyed in a way agreeable to their peculiar and respective covenant interest. And these things may not be confounded without a manifest hazard to the most important articles in the Christian religion… [T]here is no way of avoiding confusion and entanglements in our conception of these things except by keeping before our eyes the distinction between Abraham’s seed as either spiritual or carnal, and of the respective promises belonging to each. For this whole covenant of circumcision given to the carnal seed, can no more convey spiritual and eternal blessings to them as such, than it can now enright a believer (though a child of Abraham) in their temporal and typical blessings in the land of Canaan.”2

What all of these men make clear is that not only are the two seeds distinguished, one as a type of the other, but so also the blessings are distinct, one a type of the other. The dichotomy is not that they have the same promise of eternal life, but are given two ways of obtaining it (works or faith). Instead, in keeping with typology, the blessings given to Abraham’s fleshly seed are fleshly, “temporal and typical blessings in the land of Canaan.” And this typical reward was held out upon the condition of obedience. It may be added that Augustine made the same point. “Now it is to be observed that two things are promised to Abraham, the one, that his seed should possess the land of Canaan… the other far more excellent, not about the carnal but the spiritual seed, through which he is the father, not of the one Israelite nation, but of all nations who follow the footprints of his faith… what we read of historically as predicted and fulfilled in the seed of Abraham according to the flesh, we must also inquire the allegorical meaning of, as it is to be fulfilled in the seed of Abraham according to faith… In that testament, however, which is properly called the Old, and was given on Mount Sinai, only earthly happiness is expressly promised… And these, indeed, are figures of the spiritual blessings which appertain to the New Testament.”

As Coxe warns, if we do not keep the promises belonging to each distinct, we will not avoid confusion and entanglements. We must view typology in the Abrahamic dichotomy consistently. The earthly seed is given an earthly, temporal land of rest that they must work for, and this is a type of the heavenly rest that Christ worked for and gave to the spiritual seed.

This brings us to point 3 and the question of republication. The word “republication” is somewhat vague in that it can mean different things to different people. Because of this potential for confusion, clarity is improved if the word is avoided. Instead, we should simply state that the Old Covenant operated upon the works principle (Lev. 18:5). Calling the Old Covenant a republication of the Covenant of Works often leads to the confusion that the Old Covenant is the Covenant of Works. In fact, this is what Johnson says. He believes the Old Covenant offered eternal life and threatened eternal death. He makes this point in his other lecture on Hebrews 8 and the New Covenant where he argues that “Old Covenant” in Hebrews 8 refers to the Adamic Covenant of Works. Furthermore, he believes that Christ obeyed this republished Adamic Covenant of Works to earn eternal life for His people. He also believes this is the view of Nehemiah Coxe and John Owen. However, there is no reason to believe this was the view of Coxe and Owen, and it creates confusing implications. Owen was clear in his exegesis of Hebrews 8 that the first covenant being referred to was not the Adamic Covenant but was in fact a covenant that must be distinguished from it.

There was an original covenant made with Adam… This is the covenant of works, absolutely the old, or first covenant that God made with men. But this is not the covenant here intended; for, —… That first covenant made with Adam, had, as unto any benefit to be expected from it, with respect unto acceptation with God, life, and salvation, ceased long before, even at the entrance of sin… all those who receive not the grace tendered in the promise, it doth remain in fill force and efficacy, not as a covenant, but as a law… as a covenant, obliging unto personal, perfect, sinless obedience, as the condition of life, to be performed by themselves, so it ceased to be, long before the introduction of the new covenant which the apostle speaks of, that was promised “in the latter days.” But the other covenant here spoken of was not removed or taken away, until this new covenant was actually established.

Johnson mentions a few quotes from Owen and Coxe:

God did not intend in it to abrogate the covenant of works, and to substitute this in the place thereof; yea, in sundry things it re-enforced, established, and confirmed that covenant… It revived the sanction of the first covenant, in the curse or sentence of death which it denounced against all transgressors. Death was the penalty of the transgression of the first covenant: “In the day that thou eatest, thou shalt die the death.” And this sentence was revived and represented anew in the curse wherewith this covenant was ratified, “Cursed be he that confirmeth not all the words of this law to do them,” Deuteronomy 27:26; Galatians 3:10. … It revived the promise of that covenant, —that of eternal life upon perfect obedience. (Owen)

This also must not be forgotten: that as Moses’ law in some way included the covenant of creation and served for a memorial of it (on which account all mankind was involved in its curse), it had not only the sanction of a curse awfully denounced against the disobedient, but also a promise of the reward of life to the obedient. Now as the law of Moses was the same in moral precept with the law of creation, so the reward in this respect proposed was not a new reward, but the same that by compact had been due to Adam, in the case of his perfect obedience. (Coxe, p. 46)

How are we to understand these quotes if they are not teaching that the Old Covenant is the Adamic Covenant of Works, but is in fact distinct from it? Let’s start by reading the full context of Owen’s quote:

1. This covenant, called “the old covenant,” was never intended to be of itself the absolute rule and law of life and salvation unto the church, but was made with a particular design, and with respect unto particular ends. This the apostle proves undeniably in this epistle, especially in the chapter foregoing, and those two that follow. Hence it follows that it could abrogate or disannul nothing which God at any time before had given as a general rule unto the church. For that which is particular cannot abrogate any thing that was general, and before it; as that which is general doth abrogate all antecedent particulars, as the new covenant doth abrogate the old. And this we must consider in both the instances belonging hereunto. For, —

(1.) God had before given the covenant of works, or perfect obedience, unto all mankind, in the law of creation. But this covenant at Sinai did not abrogate or disannul that covenant, nor any way fulfill it. And the reason is, because it was never intended to come in the place or room thereof, as a covenant, containing an entire rule of all the faith and obedience of the whole church. God did not intend in it to abrogate the covenant of works, and to substitute this in the place thereof; yea, in sundry things it re- enforced, established, and confirmed that covenant. For, —

[1.] It revived, declared, and expressed all the commands of that covenant in the decalogue; for that is nothing but a divine summary of the law written in the heart of man at his creation. And herein the dreadful manner of its delivery or promulgation, with its writing in tables of stone, is also to be considered; for in them the nature of that first covenant, with its inexorableness as unto perfect obedience, was represented. And because none could answer its demands, or comply with it therein, it was called “the ministration of death,” causing fear and bondage, 2 Corinthians 3:7. [2.] It revived the sanction of the first covenant, in the curse or sentence of death which it denounced against all transgressors. Death was the penalty of the transgression of the first covenant: “In the day that thou eatest, thou shalt die the death.” And this sentence was revived and represented anew in the curse wherewith this covenant was ratified, “Cursed be he that confirmeth not all the words of this law to do them,” Deuteronomy 27:26; Galatians 3:10. For the design of God in it was to bind a sense of that curse on the consciences of men, until He came by whom it was taken away, as the apostle declares, Galatians 3:19. [3.] It revived the promise of that covenant, —that of eternal life upon perfect obedience. So the apostle tells us that Moses thus describeth the righteousness of the law, “That the man which doeth those things shall live by them,” Romans 10:5; as he doth, Leviticus 18:5.Now this is no other but the covenant of works revived. Nor had this covenant of Sinai any promise of eternal life annexed unto it, as such, but only the promise inseparable from the covenant of works which it revived, saying, “Do this, and live.”

Hence it is, that when our apostle disputeth against justification by the law, or by the works of the law, he doth not intend the works peculiar unto the covenant of Sinai, such as were the rites and ceremonies of the worship then instituted; but he intends also the works of the first covenant, which alone had the promise of life annexed unto them.

And hence it follows also, that it was not a new covenant of works established in the place of the old, for the absolute rule of faith and obedience unto the whole church; for then would it have abrogated and taken away that covenant, and all the force of it, which it did not.

[…]3. It will be said, as was before observed, ‘That if it did neither abrogate the first covenant of works, and come in the room thereof, nor disannul the promise made unto Abraham, then unto what end did it serve, or what benefit did the church receive thereby?’ I answer, —…

What hath been spoken may suffice to declare the nature of this covenant in general; and two things do here evidently follow, wherein the substance of the whole truth contended for by the apostle doth consist: —

(1.) That whilst the covenant of grace was contained and proposed only in the promise, before it was solemnly confirmed in the blood and sacrifice of Christ, and so legalized or established as the only rule of the worship of the church, the introduction of this other covenant on Sinai did not constitute a new way or means of righteousness, life, and salvation; but believers sought for them alone by the covenant of grace as declared in the promise. This follows evidently upon what we have discoursed; and it secures absolutely that great fundamental truth, which the apostle in this and all his other epistles so earnestly contendeth for, namely, that there neither is, nor ever was, either righteousness, justification, life, or salvation, to be attained by any law, or the works of it, (for this covenant at mount Sinai comprehended every law that God ever gave unto the church,) but by Christ alone, and faith in him.

(2.) That whereas this covenant being introduced in the pleasure of God, there was prescribed with it a form of outward worship suited unto that dispensation of times and present state of the church; upon the introduction of the new covenant in the fullness of times, to be the rule of all intercourse between God and the church, both that covenant and all its worship must be disannulled. This is that which the apostle proves with all sorts of arguments, manifesting the great advantage of the church thereby.

These things, I say, do evidently follow on the preceding discourses, and are the main truths contended for by the apostle…

4.) Into this estate and condition God brought them by a solemn covenant, confirmed by mutual consent between him and them. The tenor, force, and solemn ratification of this covenant, are expressed, Exodus 24:3-8. Unto the terms and conditions of this covenant was the whole church obliged indispensably, on pain of extermination, until all was accomplished, Malachi 4:4-6. Unto this covenant belonged the decalogue, with all precepts of moral obedience thence educed. So also did the laws of political rule established among them, and the whole system of religious worship given unto them. All these laws were brought within the verge of this covenant, and were the matter of it. And it had especial promises and threatenings annexed unto it as such; whereof none did exceed the bounds of the land of Canaan. For even many of the laws of it were such as obliged nowhere else. Such was the law of the sabbatical year, and all their sacrifices. There was sin and obedience in them or about them in the land of Canaan, none elsewhere. Hence, —

(5.) This covenant thus made, with these ends and promises, did never save nor condemn any man eternally. All that lived under the administration of it did attain eternal life, or perished for ever, but not by virtue of this covenant as formally such. It did, indeed, revive the commanding power and sanction of the first covenant of works; and therein, as the apostle speaks, was “the ministry of condemnation,” 2 Corinthians: 3:9; for “by the deeds of the law can no flesh be justified.” And on the other hand, it directed also unto the promise, which was the instrument of life and salvation unto all that did believe. But as unto what it had of its own, it was confined unto things temporal. Believers were saved under it, but not by virtue of it. Sinners perished eternally under it, but by the curse of the original law of works. And, —

(6.) Hereon occasionally fell out the ruin of that people; “their table became a snare unto them, and that which should have been for their welfare became a trap,” according to the prediction of our Savior, Psalm 69:22. It was this covenant that raised and ruined them. It raised them to glory and honor when given of God; it ruined them when abused by themselves to ends contrary to express declarations of his mind and will. For although the generality of them were wicked and rebellious, always breaking the terms of the covenant which God made with them, so far as it was possible they should, whilst God determined to reign over them unto the appointed season, and repining under the burden of it; yet they would have this covenant to be the only rule and means of righteousness, life, and salvation, as the apostle declares, Romans 9:31-33, 10:3. For, as we have often said, there were two things in it, both which they abused unto other ends than what God designed them: —

[1.] There was the renovation of the rule of the covenant of works for righteousness and life. And this they would have to be given unto them for those ends, and so sought for righteousness by the works of the law. [2.] There was ordained in it a typical representation of the way and means whereby the promise was to be made effectual, namely, in the mediation and sacrifice of Jesus Christ; which was the end of all their ordinances of worship. And the outward law thereof, with the observance of its institution, they looked on as their only relief when they came short of exact and perfect righteousness.Against both these pernicious errors the apostle disputes expressly in his epistles unto the Romans and the Galatians, to save them, if it were possible, from that ruin they were casting themselves into. Hereon “the elect obtained,” but “the rest were hardened.” For hereby they made an absolute renunciation of the promise, wherein alone God had inwrapped the way of life and salvation.

This is the nature and substance of that covenant which God made with that people; a particular, temporary covenant it was, and not a mere dispensation of the covenant of grace.

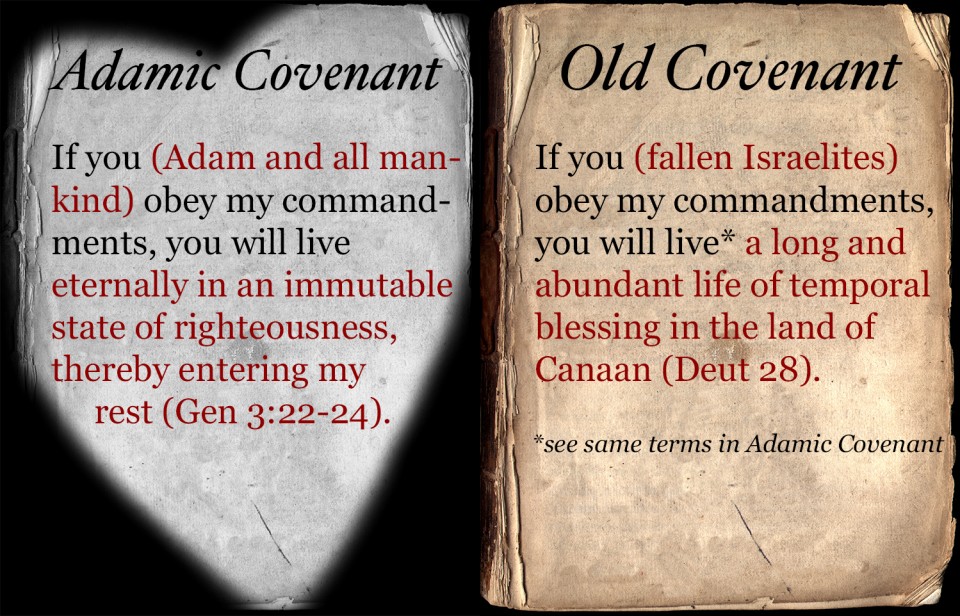

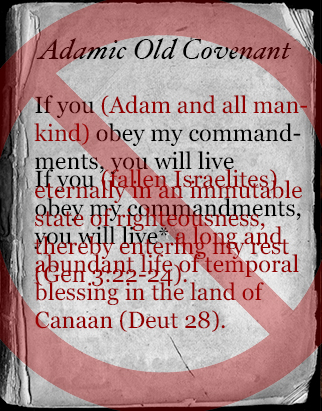

Owen is very clear that the Old Covenant was not the Adamic Covenant of Works. It was not a continuation of it. It did not offer eternal life. It did not threaten eternal death. It was “confined unto things temporal.” If that is the case, then how are we to understand their statements about the Covenant of Works being revived and represented anew? We have to first understand that there is a distinction between the law and the law as a covenant of works (see bottom of here, as well as here). With that in mind, what these men mean is that the Old Covenant did, in fact, share something with the Adamic Covenant: 1) the moral law, and 2) the works principle. The Old Covenant said “Obey my commandments, and you will live in Canaan and be blessed” (Lev 18:5). “Obey my commandments, and you will live” was the same condition as the Adamic Covenant. But “live” is meant in two different senses. If we imagine the two covenants as contracts or covenant documents, there would be a footnote next to Leviticus 18:5 which says “See the original Adamic Covenant of Works.” In this way, Israel was reminded of that original covenant – a covenant that they did not have a written record of. The Old Covenant and the book of the law was written in order for Israelites, and by extension us, to understand the unwritten Adamic Covenant.

And so this is how it was “revived” in the minds of the Israelits as a “memorial.” It’s something written on every man’s heart. Coxe explains “They expect a reward of future blessedness for their obedience to the law of God and to stand before him on the terms of a covenant of works. This necessarily arises from man’s relationship to God at first in such a covenant (which included the promise of such a reward) and the knowledge of these covenant terms communicated to him, together with the law of his creation.” (45) And so when fallen man sees these terms written out for him, the terms of the original covenant written on his heart are revived and represented anew.

Owen later explains the overlap in the works principle:

Obs. IX. The promises of the covenant of grace are better than those of any other covenant, as for many other reasons, so especially because the grace of them prevents any condition or qualification on our part. —I do not say the covenant of grace is absolutely without conditions, if by conditions we intend the duties of obedience which God requireth of us in and by virtue of that covenant; but this I say, the principal promises thereof are not in the first place remunerative of our obedience in the covenant, but efficaciously assumptive of us into covenant, and establishing or confirming in the covenant. The covenant of works had its promises, but they were all remunerative, respecting an antecedent obedience in us; (so were all those which were peculiar unto the covenant of Sinai)…

The greatest and utmost mercies that God ever intended to communicate unto the church, and to bless it withal, were enclosed in the new covenant. Nor doth the efficacy of the mediation of Christ extend itself beyond the verge and compass thereof; for he is only the mediator and surety of this covenant. But now God had before made a covenant with his people. A good and holy covenant it was; such as was meet for God to prescribe, and for them thankfully to accept of. Yet notwithstanding all the privileges and advantages of it, it proved not so effectual, but that multitudes of them with whom God made that covenant were so far from obtaining the blessedness of grace and glory thereby, as that they came short, and were deprived of the temporal benefits that were included therein…

For whereas l[‘B’ signifies a “husband,” or to be a husband or a lord, b being added unto it in construction, as it is here, yTil][‘B; μb;, it is as much as “jure usus sum maritali,” —’I exercised the right, power, and authority of a husband towards them; I dealt with them as a husband with a wife that breaketh covenant:’ that is, saith the apostle, ‘“ I regarded them not” with the love, tenderness, and affection of a husband.’ So he dealt indeed with that generation which so suddenly brake covenant with him. He provided no more for them as unto the enjoyment of the inheritance, he took them not home unto him in his habitation, his resting-place in the land of promise; but he suffered them all to wander, and bear their whoredoms in the wilderness, until they were consumed. So did God exercise the right, and power, and authority of a husband towards a wife that had broken covenant. And herein, as in many other things in that dispensation, did God give a representation of the nature of the covenant of works, and the issue of it.

So according to Owen, the Old Covenant was a covenant of works (for life in Canaan), but it was not the Covenant of Works. It “republished” the covenant of works insofar as it said “Do this and live.”

New Testament interpretation of the Old Covenant

The question may then arise, “Why then does Paul seem to refer to the Old Covenant as the Covenant of Works?” In the Q&A, Jeffery Johnson notes:

I want to emphasize that when the New Testament’s talking about the Mosaic Covenant– Now, if you read the Old Testament, it’s mainly dealing with the transient, temporal aspects of it. You can’t get away, reading the Old Testament, knowing that’s a heavy emphasis of the Old Testament. But when you read the New Testament interpretation of the Old, the New Testament authors are heavily emphasizing the eternal aspect of that law, the condemnation of the law, and the guilt of that law. I think that’s what Paul’s doing in Romans. I think that’s what’s emphasized in the book of Hebrews. And that wants to be my emphasis. The Mosaic Covenant has the two aspects, but I don’t want that first aspect to be minimized. The Mosaic Covenant does remind us that you have to be righteous to go to heaven. It’s not that the Mosaic Covenant established that. That was already established.

Notice the point: the Old Testament seems to speak one way, but then the New Testament interprets it a different way. This pattern is common in the New Testament, but the way we explain it is through typology. If you read John 19:36, John says there was a prophecy about Christ’s crucifixion in Exodus. But if you go back and read Exodus 12:46, the verse says nothing about Christ. It was referring to the actual lamb of the passover meal. But John makes a series of logical deductions in light of his understanding of typology (that the Old Testament sacrifices were typological of Christ) and simply states that this was a prophecy of Christ that his bones should not be broken. He doesn’t show each step in his logical argument comparing the paschal lamb to Christ, the true Paschal Lamb. He just states the conclusion. Technically speaking, this is known as an enthymeme, but it is a very common part of everyday speech. This is how we are to understand the typological interpretation of the OT by the NT. The Mosaic Covenant itself does not list eternal life as a blessing or reward, but when it is applied typologically in the NT, it does say something about eternal life as a reward for works. Pascal Denault noted right after Johnson’s previous statement:

Denault: So you would say that formally the Mosaic Covenant is bound to earthly realities, in itself, and it’s only typologically showing the eternal or heavenly realities?

Johnson: Formally speaking– but because it is a republication of that Covenant of Works, you can’t ever disjoin or separate that eternal, moral condition of the covenant of works. If you take the covenant of works given to Adam, and say that didn’t exist, I think the Mosaic Covenant itself would fall apart. If that makes sense. How can it be a republication if there wasn’t anything to republish? And that was one of the main functions of it to stop everyone’s mouth before God. If the Mosaic Covenant, if all it was, was just temporal obedience and relative obedience for temporal blessings, well maybe the Pharisees had a right to say, “I can do that.” There was generations that was blessed by God and received some of the temporal blessings. How does that condemn them? If it was just that side of it, how does that cause the nation of Israel to shut their mouth and say “I am guilty before God.”

Denault: Because we make a distinction between the moral law and the Mosaic Covenant itself. So it’s true there is this eternal condemnation that comes with the law of Moses–

Johnson: Which already existed. This is what Owen said. The Mosaic Covenant in and of itself doesn’t save or condemn anybody, in and of itself. It does show us that we already are condemned. And it does show us how we are redeemed in Christ and how he fulfills the moral law.

Denault: I think it’s an important distinction to say it’s something to reveal, or to actually do it.

The way to understand the New Testament interpretation and application of the Old Covenant is through typology. The Old Covenant revealed information about the Covenant of Works by way of typology, but it was not the Covenant of Works. Just as the paschal lamb revealed information about The Paschal Lamb, but the paschal lamb was not Christ. Just as the paschal lamb can exist apart from and be separated/distinguished from Christ, so too can the Mosaic Covenant exist apart from and be separated/distinguished from the Covenant of Works. Of course the paschal lamb’s full significance can only be understood by it’s relation to Christ – but that does not mean it is Christ. And the Mosaic Covenant’s full significance can only be understood by its relation to the Covenant of Works (as well as the Covenant of Works as fulfilled by Christ) – but that does not mean it is the Covenant of Works.

Bryan Estelle notes “[T]he life promised upon condition of performing the statutes and judgments in its immediate context in Leviticus here is ‘the covenantal blessing of abundant (and long) life in the land of Israel.’… [Now in Paul’s day] Israel’s disobedience has triggered the curse sanctions [of the Old Covenant]. Therefore, the new covenant context has essentially changed matters here… What was prototypical [life in Canaan] has been eclipsed by what is antitypical [eternal life].” And therefore Paul appeals to the written Old Covenant to make various points about the Adamic Covenant (which was not written anywhere for him to directly quote), because of the overlap of law and works principle (as illustrated in the image above).

(Note: to see an elaboration of Denault’s answer to Johnson’s question about how the moral law functioned for national temporal curse vs. individual eternal condemnation, see here).

In sum, Richard Barcellos notes:

However one views the Mosaic Covenant, it cannot be a republication of the Covenant of Works as it stood with Adam. This is so for at least two reasons: first, Adam was sinless; and second, Adam represented others. Israel was neither sinless nor representative of others. So if we view the Mosaic Covenant as republishing something of the Covenant of Works, it cannot be the essence and substance of that covenant on its original terms. It may be (and I think it is) a republication of certain principles of the original Covenant of Works, but for different purposes than initially given.

We must be careful to distinguish the two because great confusion and contradiction results when we do not. Identifying the Old Covenant with the Adamic Covenant of Works creates exegetical, logical, and confessional problems. As Owen demonstrated, exegetically it does not fit with the text of Hebrews 8, and Owen’s entire argument proceeds upon this basis. If one identifies the Old Covenant with the Adamic Covenant of Works, Owen’s rigorous deduction and accurate analysis of the nature of the covenant of grace revealed/established must be rejected. Simply follow Owen’s argument here to see.

Logically this winds up creating the same type of problem we are rejecting in the paedobaptist’s substance/administration view. It rejects the substance/administration view of the covenant of grace and replaces it with a substance/administration view of the covenant of works. It eliminates careful distinctions between the biblical covenants and combines them into one. Doing so results in several contradictions. The claim that Christ fulfilled the Old Covenant as the Adamic Covenant of Works creates an irreconcilable contradiction in that it claims Christ was under Adam’s federal headship, and therefore not sinless (contradicting LBCF 8.2). The biblical and confessional teaching is that Christ was born of a virgin and was therefore not under Adam’s federal head, meaning he was not under the Adamic Covenant of Works. Claiming that the Old Covenant is the Adamic Covenant of Works denies this since Christ was, as Abraham’s physical seed, under the Old Covenant. Christ did fulfill a covenant of works for eternal life, but it was his own covenant of works: the Covenant of Redemption/New Covenant, of which he is the federal head.

Furthermore, saying the Old Covenant is the Adamic Covenant of Works requires Old Covenant saints to simultaneously be in Christ and in Adam: in the covenant of grace and in the covenant of works. This contradicts LBCF 19.6. Moses was certainly a member of the Mosaic Covenant. Moses was certainly saved and thus under Christ’s federal headship. Moses was both of these at the same time: under Christ and in the Old Covenant. Therefore the Old Covenant was not the Adamic Covenant of Works.

Again, the solution to this dilemma is the recognition that a particular covenant can reveal another covenant without being that covenant. The Abrahamic Covenant can reveal the Covenant of Grace without being the Covenant of Grace. Likewise, the Old Covenant can reveal the Adamic Covenant of Works without being the Adamic Covenant of Works. In this way Paul can appeal to the Old Covenant to make a point about the Adamic Covenant of Works, just as he can appeal to the Abrahamic Covenant to make a point about the Covenant of Grace. For more on this, see Samuel Renihan’s Form and Matter in Covenant Theology and Form and Matter + Promise and Promulgation = Particular Baptist Federal Theology.

We still have a lot of work to do in fleshing out our covenant theology and presenting it to others (since 17th century writings are not the final word), but if we are careful in reading some of these men, we can avoid rehashing points they already worked out.

Johnson’s discussion of contemporary challenges was a helpful call to clarify the essential points of 1689 Federalism and to proceed with humility as we discuss with each other and seek to teach others about it. In light of the above, a modified 5 points of 1689 Federalism might be:

- There was a pre-fall covenant made with Adam, and it was the Covenant of Works.

- There is a dichotomy to the Abrahamic Covenant. (Properly/consistently understood via typology)

- The Old Covenant functioned according to the works principle (Lev 18:5). (Properly/consistently understood as limited to temporal blessing and curse in the land of Canaan)

- The third use of the moral law.

- The New Covenant alone is the Covenant of Grace. (The most essential point)

Jeffery Johnson and Pascal Denault have done great work writing on baptist covenant theology and Heritage Baptist Church has done great work in hosting a conference on the Distinctives of Baptist Covenant Theology. May the Lord bless the ongoing work.

See also:

- Additional Answers to 2015 Founders Conference Q&A

- Republication, the Mosaic Covenant, and Eternal Life